Adventure in United Arab Emirates

In 2018, I moved out to the UAE for only 3 months. I worked for RENECO, a company specialized into Houbara bustard captive-breeding. This experience was quite unique, navigating between the captive-breeding facility at the National Avian Research Centre (NARC) in Suweihan (middle of the desert) to Abu Dhabi where my office was located.

My work focused on the epidemiological aspects (qualitative and quantitative) of some important diseases Houbara bustards can get.

Some papers to know more about bustards:

https://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/27442/1/HIRSCHINGER_Julien.pdf (In French)

Diversity of avipoxviruses in captive-bred Houbara bustard.

Guillaume Le Loc'h et al. Veterinary Research 2014, 45:98

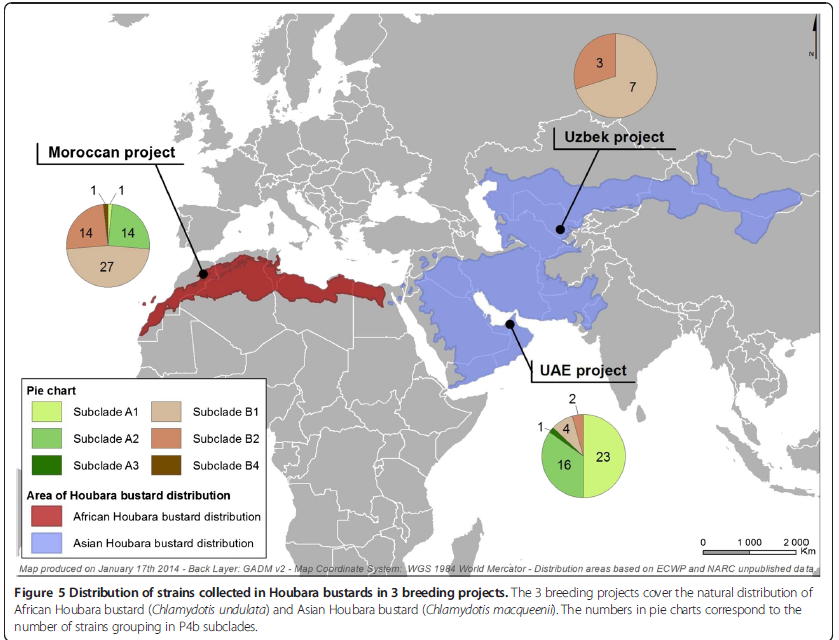

Implementation of conservation breeding programs is a key step to ensuring the sustainability of many endangered species. Infectious diseases can be serious threats for the success of such initiatives especially since knowledge on pathogens affecting those species is usually scarce. Houbara bustard species (Chlamydotis undulata and Chlamydotis macqueenii), whose populations have declined over the last decades, have been captive-bred for conservation purposes for more than 15 years. Avipoxviruses are of the highest concern for these species in captivity. Pox lesions were collected from breeding projects in North Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia for 6 years in order to study the diversity of avipoxviruses responsible for clinical infections in Houbara bustard. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of 113 and 75 DNA sequences for P4b and fpv140 loci respectively, revealed an unexpected wide diversity of viruses affecting Houbara bustard even at a project scale: 17 genotypes equally distributed between fowlpox virus-like and canarypox virus-like have been identified in the present study. This suggests multiple and repeated introductions of virus and questions host specificity and control strategy of avipoxviruses. We also show that the observed high virus burden and co-evolution of diverse avipoxvirus strains at endemic levels may be responsible for the emergence of novel recombinant strains.

Low Impact of Avian Pox on Captive-Bred Houbara Bustard Breeding Performance

Guillaume Le Loc'h Front. Vet. Sci., 13 February 2017

Avian pox, a disease caused by avipoxviruses, is a major cause of decline of some endangered bird species. While its impact has been assessed in several species in the wild, effects of the disease in conservation breeding have never been studied. Houbara bustard species (Chlamydotis undulata and Chlamydotis macqueenii), whose populations declined in the last decades, have been captive bred for conservation purposes for more than 20 years. While mortality and morbidity induced by avipoxviruses can be controlled by appropriate management, the disease might still affect bird breeding performance and jeopardize the production objectives of conservation programs. Impacts of the disease was studied during two outbreaks in captive-bred juvenile Houbara bustards in Morocco in 2009-2010 and 2010-2011, by modeling the effect of the disease on individual breeding performance (male display and female egg production) of 2,797 birds during their first breeding season. Results showed that the impact of avian pox on the ability of birds to reproduce and on the count of displays or eggs is low and mainly non-significant. The absence of strong impact compared to what could be observed in other species in the wild may be explained by the controlled conditions provided by captivity, especially the close veterinary monitoring of each bird. Those results emphasize the importance of individual management to prevent major disease emergence and their effects in captive breeding of endangered species.

Avian Paramyxovirus Type 1 Infection in Houbara Bustards (Chlamydotis undulata macqueenii): Clinical and Pathologic Findings

Thomas A. Bailey, et al. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine Vol. 28, No. 3 (Sep., 1997),

Clinical and pathologic findings of avian paramyxovirus type 1 (PMV-1) in 19 houbara bustards (Chlamydotis undulata macqueenii) imported from Pakistan into the United Arab Emirates and one captive-bred bird are reported. Clinical signs included circling, walking backward, ataxia, opisthotonos, torticollis, recumbency, head tilt, head shaking, head tremor, tucking of head under keel, nasal discharge, conjunctivitis, and diarrhea. The length of time imported birds exhibited clinical signs varied from 4 days to 18 mo after importation. Hemagglutinating antibodies against PMV-1 were detected in the sera of all 17 birds from which blood samples were collected, and PMV-1 was isolated from pooled brain, spleen, and lung tissues from two birds with acute clinical signs. There were no distinctive gross lesions at necropsy, and histologic findings were consistent with but not pathognomonic for PMV-1. All houbara bustards managed in a captive breeding and restoration program established by the National Avian Research Center have been vaccinated against PMV-1 since October 1992, and no case of PMV-1 has been reported in this collection since that time.

Medical dilemmas associated with rehabilitating confiscated houbara bustards (Chlamydotis undulata macqueenii) after avian pox and paramyxovirus type 1 infection

Thomas A Bailey et al. J Wildl Dis . 2002 Jul;38(3):518-32.

Projects to rehabilitate confiscated animals must carefully consider the risks of disease when determining whether to release these animals back into the wild or to incorporate them into captive breeding programs. Avipox and paramyxovirus type 1 (PMV-1) infections are important causes of morbidity and mortality during rehabilitation of confiscated houbara bustards (Chlamydotis undulata macqueenii). This paper presents key findings of an intensive health monitoring program (physical condition, hematology, serology, endoscopy, microbiology, and virology) of two flocks of houbara bustards that survived outbreaks of septicemic avipox and PMV-1 respectively. Mortality in each flock from avipox and PMV-1 infections were 47% and 25% respectively, and the clinicopathologic features and management of each outbreak are presented. Avipox and PMV-1 viruses were not isolated from surviving birds monitored monthly for 11 mo after initial infection nor were septicemic or diptheritic avipox and PMV-1 infections detected in the captive breeding collection into which surviving birds were ultimately integrated up to 24 mo later. Adenovirus was isolated from four birds during the study demonstrating that novel disease agents of uncertain pathogenicity may be carried latently and intermittently shed by confiscated birds. This paper demonstrates the risk of importing pathogens with illegally traded houbara bustards and reinforces the need for surveillance programs at rehabilitation centers for these birds. We recommend that confiscated houbara bustards integrated into captive breeding programs be managed separately from captive-bred stock. Other measures should include separate facilities for adult birds and rearing facilities for offspring derived from different stock lines and strict sanitary measures. Additionally, health monitoring of confiscated birds should continue after birds are integrated into captive flocks.

Antibody response of kori bustards (Ardeotis kori) and houbara bustards (Chlamydotis undulata) to live and inactivated Newcastle disease vaccines

T A Bailey, U Wernery, J H Samour, J L Naldo. J Zoo Wildl Med. 1998 Dec;29(4):441-50.

Adult houbara bustards (Chlamydotis undulata) and juvenile kori bustards (Ardeotis kori) were given four regimens of commercially available inactivated and live poultry paramyxovirus type 1 (PMV-1) vaccines. Immunologic response to vaccination was assessed by hemagglutination inhibition assay of serum. Kori bustards, to which a dose of 0.5 ml of a commercially available inactivated vaccine for poultry had been administered intramuscularly (0.15 ml/kg body weight), failed to develop hemagglutinating antibodies, but antibody titers of low intensity and duration were detected following administration of a second and third subcutaneous dose of 2.0 ml vaccine per bird (0.40-0.45 ml/kg). In subsequent trials, when inactivated vaccine was administered subcutaneously at 1.0 ml/kg body weight following two or four live vaccinations administered by the ocular route, juvenile kori bustards developed higher, more persistent titers of antibodies. Kori bustards given four live vaccinations followed by inactivated vaccine developed higher titers of longer duration compared with kori bustards given two live vaccines followed by inactivated vaccine. Antibody titers of kori bustards given inactivated vaccine were higher and more persistent than the antibody response to live vaccination. Houbara bustards, previously vaccinated with inactivated vaccine, that were given a booster dose of inactivated vaccine maintained high mean antibody titers (> or = log, 5) for 52 wk. The authors recommend that inactivated PMV-1 vaccine should be administered by subcutaneous injection of 1.0 ml/kg vaccine to bustards. Adult bustards, previously vaccinated with inactivated vaccine, should be vaccinated annually with inactivated vaccine. Juvenile bustards should receive a second dose of inactivated vaccine 4-6 mo after the first dose of inactivated vaccine. Even though inactivated PMV-1 vaccines induced hemagglutination inhibition antibodies and produced no adverse reactions, further studies will be required to determine the protective efficacy of the antibody.

Antibody response to Newcastle disease vaccination in a flock of young houbara bustards (Chlamydotis undulata)

S Ostrowski, M Saint-Jalme, M Ancrenaz. J Zoo Wildl Med. 1998 Jun;29(2):234-6.

Twelve young houbara bustards (Chlamydotis undulata) were vaccinated with a lentogenic strain of Newcastle disease virus. Another seven birds were kept in close contact with the treated flock but were not vaccinated. Antibody levels were measured in all birds with hemagglutination inhibition test over the course of 1 yr. Antibody formation with no side effects was observed in 18 birds. The duration and amplitude of the antibody response differed between the groups.